Is it possible for a 20th century poet to be a contemporary? David Gascoyne, who died in 2001—just managing to dip his toes into the third millenium—is a special case. A first biography of the cultic but widely overlooked poet has been published in 2012, Night Thoughts by Robert Fraser. This finely wrought Oxford University Press tome by the man who resurrected the reputation of George Barker might serve to make England wonder about the nature of achievement in the field of poetry. The Dracula-like presence of Gascoyne is emerging from his coffin, a benign vampire, a blood donor. He walks. His breath makes patterns. Many of the most successful poets writing today will never have biographies written about them. They’re not interesting enough. Name England’s most important 20th century poets… Hardy, Auden, Bunting, Hill? Many say Philip Larkin. The 20th century’s mistake was to think it could judge itself. It will have to be judged posthumously, not by anthologies brought out for the Christmas market in the year 2000. England doesn’t know itself poetically because it doesn’t know David Gascoyne, but it is going to have to get to know him. His quarantine is over. The plates are shifting. As Hopkins was a 19th century poet who became widely known in the 20th, I believe Gascoyne is a star of the future, an essential English messenger, a politico-religious poet.

Jokingly, I call him ‘the real T.S Eliot’ though I don’t know what this means. Certainly, Gascoyne is my favourite English poet of the 20th century. Eliot, an American regarded as the greatest poet in any language of the 20th century, is unassailable. Also, he has become a naturalised English poet, a Tory guru, the thin-blooded ‘mentor’ of such right-wing cheerleaders as Roger Scruton. However, when I re-examine Eliot’s tiny oeuvre with its many second-rate poems, I wonder why he is such an icon. His few masterpieces are too well-known, and seem museum-pieces of modernism. They exist for undergraduates who will be unwittingly exposed to the subliminal advertising of the Anglo-Catholic, Classicist, Royalist hymn-sheet. Gascoyne’s oeuvre is, by comparison, so unknown, so off-campus, so strange and illegitimate and unpropped, that it seems more like silvery manna than any human bread. Its profundity, radicalism, spirituality and bohemianism are unique. His left-wing genius was extended by Surrealism, and later by Existentialism, he being the first Englishman to fully immerse himself in both movements. In France, he is probably also an underground legend. He formed deep relationships with outstanding people across the Channel; Blanche Jouve was his therapist; he was Pierre Jean Jouve’s translator. His exemplary French connection aroused the hostility of his British peers, who ignored his aesthetic imports. Perhaps the most emblematic vista of his lack of success was that instead of being summoned to Buckingham Palace to be honoured by the Queen of England or to the Elysée Palace by the President of France, he took it upon himself to break into both buildings while suffering from amphetamine psychosis. He is the most out-there major poet of modern times. This repels bourgeois readers, so far. It’s understandable. Most English poets if given the choice would prefer an MBE to a straitjacket, though others wouldn’t see any difference.

Jokingly, I call him ‘the real T.S Eliot’ though I don’t know what this means. Certainly, Gascoyne is my favourite English poet of the 20th century. Eliot, an American regarded as the greatest poet in any language of the 20th century, is unassailable. Also, he has become a naturalised English poet, a Tory guru, the thin-blooded ‘mentor’ of such right-wing cheerleaders as Roger Scruton. However, when I re-examine Eliot’s tiny oeuvre with its many second-rate poems, I wonder why he is such an icon. His few masterpieces are too well-known, and seem museum-pieces of modernism. They exist for undergraduates who will be unwittingly exposed to the subliminal advertising of the Anglo-Catholic, Classicist, Royalist hymn-sheet. Gascoyne’s oeuvre is, by comparison, so unknown, so off-campus, so strange and illegitimate and unpropped, that it seems more like silvery manna than any human bread. Its profundity, radicalism, spirituality and bohemianism are unique. His left-wing genius was extended by Surrealism, and later by Existentialism, he being the first Englishman to fully immerse himself in both movements. In France, he is probably also an underground legend. He formed deep relationships with outstanding people across the Channel; Blanche Jouve was his therapist; he was Pierre Jean Jouve’s translator. His exemplary French connection aroused the hostility of his British peers, who ignored his aesthetic imports. Perhaps the most emblematic vista of his lack of success was that instead of being summoned to Buckingham Palace to be honoured by the Queen of England or to the Elysée Palace by the President of France, he took it upon himself to break into both buildings while suffering from amphetamine psychosis. He is the most out-there major poet of modern times. This repels bourgeois readers, so far. It’s understandable. Most English poets if given the choice would prefer an MBE to a straitjacket, though others wouldn’t see any difference.

The poems, the stories of the sacrifices it took to make them, are disseminating. The biography helps us to fuse the life and the art, and see the legend whole. I did not realise, for instance, the story behind his classic poem A Vagrant. The poem is in quotation marks so I had thought Gascoyne was ventriloquising a beggar he had encountered. But no, it was actually himself, homeless in Paris on his 31st birthday, Rimbaud as a mature man. Its sprightly voice, its out-there odyssey, really give a sense of what’s at stake — the cruelty of the megalopolis, the stoicism of humanity. There’s nothing like it. Voices within the voice add soupçons of madness, a sheep breaks in, but the voice retains its crispness. It’s fascinating. If Jean Genet read it he’d have been flabbergasted. Gascoyne himself becomes a genie of the streets and quays herein. The experience offers him an incredible vantage-point, and a sympathetic eye to see through the stone-walling city:

the soul

Is said by some to be a bourgeois luxury, which shows

A strange misunderstanding both of soul and bourgeoisie.

It is both Paris and Atlantis, a poem of urban shamanism. We could almost be grateful for the poverty that enabled him to see what he saw, write what he wrote. Kathleen Raine, a friend and travelling companion on a reading tour of America, notes that he regarded himself as a ‘vagrant’. Safety-netless, his acrobatics are all the more breathtaking. Though he could fall to his death, he doesn’t. In an era in which homelessness is rightly regarded as ‘The Big Issue’, this is an illuminating poem on the theme. Like Rimbaud before him and Dylan after him he attunes to the ‘mystery tramp’, partakes of the Chaplinesque aura, dustbinning academies in the process.

The city, no matter what city, is always Dis, as in a free sonnet Inferno:

One evening like the years that shut us in,

Roofed by dark-blooded and convulsive cloud,

Led onward by the scarlet and black flag

Of anger and despondency, my self:

My searcher and destroyer: wandering

Through unnamed streets of a great nameless town,

As in a syncope, sudden, absolute,

Was shown the void that undermines the world:

That he was a teenage genius adds to his lustre. The 19-year-old friend of Eluard, encouraged by the Frenchman, wrote his First English Surrealist Manifesto in 1935, against a backdrop of Royalist jingoism. Published in the new biography and translated by Robert Fraser from Gascoyne’s own French, it seems eerily relevant to the England of 2012 in the throes of Diamond Jubilee. ‘At the very moment at which we are composing these lines in London (May 1935), the whole of England—orchestrated by the capitalist press—is preparing for an hysterical frenzy of the most dispiriting kind: the Silver Jubilee. May one not discern in this fact a manifestation of historic justice? Just when the country is enjoined by its government to a travesty of rejoicing in the names of patriotism and imperialism, despair is the principal reaction of the poets.’ To read this for the first time in 2012, alongside a contemporary poem such as Heathcote Williams’ Royal Babylon, was doubly exhilarating. Gascoyne was joining in with the zeitgeist, lending his neglected weight to the resistance. For poets wondering if politicised poetry was less than poetry, his manifesto offers an assurance: ‘Qualified poets are not confronted with a stark choice between two directions: on the one hand the pursuit of a simplified art, populist and proletarian and possessing no purpose beyond the efficacy of its propaganda or, on the other hand, de-politicised art, subjective in the extreme, aspiring to nothing save the personal expression of the writer. Surrealism indicates a third way, the only authentic one, leading victoriously out of the twin traps on which the first two approaches are impaled.’ Today a poet can read this and—without having to walk lobsters on Oxford Street—know there is nothing second-rate about political poetry. Ginsberg demonstrated it in the 20th century to a vast congregation, but Gascoyne is still being debriefed. (The two poets enjoyed a late-flowering friendship and can be seen in the Italian documentary ‘Lunatics, Lovers and Poets.’)

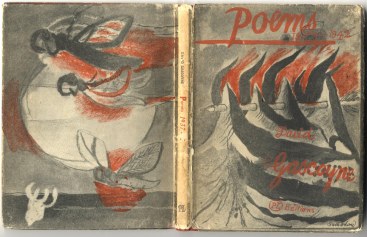

There is as yet no Complete Poems of Gascoyne. What you get looking into various selections and collections is a miraculously stylish 20th century: Surrealism, WW2, Existentialism, psychogeography. His Surrealist poems are from a distinct phase (1933-36) and never overburden the oeuvre. He is along with Dylan Thomas and Bob Dylan one of the few poets in English to make Surrealism work. Today when English poetry is attached to a life-support machine called social realism, his example is not only a third way but a way out. His most anthologised Surrealist poem is the beautiful And the Seventh Dream is the Dream of Isis which came before Robert Graves’ The White Goddess but speaks to all those who’d prize the Gravesean flame above the Larkinian squib:

she was standing at the window clothed only in a ribbon

she was burning the eyes of snails in a candle

she was eating the excrement of dogs and horses

she was writing a letter to the president of france

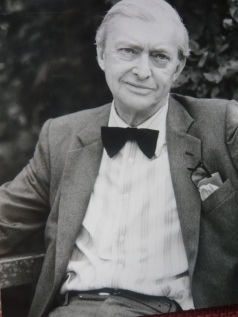

His World War Two poems are much less known than those of Dylan Thomas or, say, W.H Auden’s September 1, 1939 and the third part of his elegy for Yeats. They fill a huge void, the void of their own absence from English anthologies. They are still cultic rather than a cornerstone of the cultural heritage. Unlike Auden, Gascoyne didn’t flee England, but returned to England from France. He would rather have served in the army than be imprisoned as a conscientious objector, but was classed as a Grade 3 conscript, i.e unlikely to be called up and only suitable for sedantary work. A great anecdote tells how he was in the company of George Barker as bombs were landing on Hammersmith. When Barker turned to look at Gascoyne he saw his friend in immaculate suit and bow-tie reciting Baudelaire, in French, to a mouse in the fireplace. Gascoyne—following in the footsteps of his theatrical forbears, the Emerys—enjoyed an unlikely career as a professional actor during the war. His suite of World War Two poems is atmospherically painted on large-scale canvases. One of them, Zero, from September 1939, is a dizzying vision of the abyss that would apply to any human situation in which catastrophe is imminent. It speaks as powerfully to our time as any poem I can think of, staring into the eye of the apocalypse:

Who can by now not hear

The hollow and annihilating roar

Of final disillusion; or not know

How our condition is uncertain and obscure

And difficult to to bear? Yet through

The blackness of his dungeon there still peer

Man’s eyes, unmoving, lit by their desire

To see the worst, and yet not die

Of their lucid despair

But in such vision persevere

Through time into Eternity.

For this is Zero-hour

This is surely one of Gascoyne’s inimitable talents, seeing into the heart of the matter, going beyond polite emotion, assizing the gravity of the human situation, expressing it with gravitas. It earns its exclamation mark. The English reading public, steeped in Kipling’s ‘If you can keep your head while all about you are losing theirs’ clearly have no time for this sort of thing. ‘Keep calm and carry on’ is preferable to the ‘incoherent Nada of the seer’. Though Zero is too truthful to court popularity it is nonetheless possessed of the brilliance of a great popular song. Why are Eliot’s dirges better known than this? It is surely the implied critique of Conservatism in such poems as Eros Absconditus that debars advancement, say, the damning alexandrine: ‘In blind content they breed who never loved a friend’. A rare example of the poet-as-artist, his freethinking is enabled by his bohemianism, the abandon of imagination. (It was a later poet-as-artist, Jeremy Reed, a brilliantly distinguished and unaccountably marginalized protégé, who first alerted me to Gascoyne’s importance.) Such a poet inspires artists working in other media. An Englishman who did get Gascoyne was the actor/writer Simon Callow. He describes Gascoyne’s 1978 joint reading with Stephen Spender at The Roundhouse:

The voice that emerged from the hunched, haunted man was, by comparison with Spender’s bold clarity, feeble, despite the microphone in front of him… The passion gripped him, a strange vatic figure, now become Beckett-like, nothing but burning eyes and a mouth urgently speaking of isolation endured and alienation transfigured, of pain universal and particular, of high noon and eclipse. He spoke of these things with a presentness and a personal truth which was more than moving: it was nearly unbearable. The man’s life had been a sort of ‘via crucis’; he knew whereof he spoke… ‘Ecce Homo’. The memory of the generalised seventeen-year-old emotionalism I had brought to the poem… made me blush in the face of this authenticity, these molten feelings poured into a cast of such precision. It was the stubborn pursuit of the precise word, the exact image as a conduit for the expression of experience that Gascoyne, in his reading, made so evident.

The poem Ecce Homo from the sequence Miserere is proof of further repulsions. Gascoyne writes Christian poems. Though Eliot’s and R.S Thomas’s and Geoffrey Hill’s Christianity-in-lyricism is palatable, Gascoyne’s must be kept at arm’s length. What’s wrong? It’s simple. Gascoyne’s Christianity is that of Blake, of Coppe, of the millenarians and Gnostics. ‘Christ of Revolution and of Poetry’ is the startling refrain. One really doesn’t get better crucifixion poems than this; it is the equal of a painting by an Old Master, yet it is updated to the Fascist era. The whole sequence Miserere is evidence of his religious existentialist quest, via friends such as Pierre Jean Jouve and Benjamin Fondane, as well as the posthumously influential Kierkegaard. There are many self-styled humanists who would refuse to read Christian poetry, but they are foolish. The purpose it serves, certainly at Gascoyne’s level, is not to proselytise or even to pray, but to wrestle with Christendom. None of us can deny that we are surrounded by Christian architecture, iconography, educational and charitable institutions, tourist rubble etc. Our ancestry is Christian, our guilt is Christian and the wars we watch on television being fought in our name are Christian also. Even our nihilism is Christian. True Christian poetry is a critique of Christendom, which is, after all, the superstructure of capitalism. As poetry cleanses the language, it cleanses the superstructure. Secular poetry, afraid of metaphysical ideas, afraid of the cobwebs in the corner of the ceiling, only goes so far. That Gascoyne is a latter-day Christian mystic only makes him all the more repulsive in neo-Darwinian England. The establishment embraced Eliot’s hymns and Eliot himself, but Gascoyne was much more the Christian hermit, undistracted by office jobs. Eliot himself, as publisher, rebuffed Gascoyne the poet. Stephen Spender confessed that he and Eliot—both from haut-bourgeois backgrounds—didn’t wish to share a carpet with Gascoyne for fear of the traces he might leave on it. Spender also confessed envy. But how the held-down poet later soars, as if the holding-down was a bow-string.

And we must never sleep during that time!

He is suspended on the cross-tree now

And we are onlookers at the crime,

Callous contemporaries of the slow

Torture of God. Here is the hill

Made ghastly by His spattered blood

Whereon He hangs and suffers still;

See, the centurions wear riding-boots,

Black shirts and badges and peaked caps,

Greet one another with raised-arm salutes;

They have cold eyes, unsmiling lips;

Yet these His brothers know not what to do.

Gascoyne’s anti-Fascism, anti-imperialism, anti-capitalism, anti-patriotism therefore can contribute much to our time, to the current debates, especially in the apocalypse-tinged year of 2012. The Occupy protesters of St. Paul’s were not afraid to taunt Christian capitalism, and the city of London, with the question ‘What Would Jesus Do?’ Gascoyne’s Christian poems are formulated in the same spirit, and add a mocking ‘What would Pontias do?’

The poem Demos in Oxford Street—with its richly ambiguous ‘Demos’–seems to evoke the spirit of a one-man May Day protester in the heart of the satanic malls:

…the mature

And really average population passing by, away

And onward down this thoroughfare, of all surely the most

Average in any modern capital. O Sting!

Where is our life? Where is my neighbour, Love?

We have hardened our faces against each other’s weariness

Who walk this way; we are not bound to one another

By bomb panic or famine and it is not Christmas Day.

We are aware of Socialists in power at Westminster

Who seem to be making a pretty mess of things…

(Needless to say, his seeming anti-Socialism here does not imply Conservatism but a disgust with the Labour Party. Though he was capable of lapsing to the right, he was always more than capable of relapsing to the left).

‘The real T.S Eliot’ has for a ‘Waste Land’ given us the radiophonic poem ‘Night Thoughts’. It is another unknown, ineffable goldmine, a great meditation on London written by a native Londoner, one whose mystical attunement to the city was a birthright. One of many voices is called the ‘Anonymous Mass Voice’ and this is one of the poem’s arias:

Fear, fear: you speak of fear.

What is this fear? Is it the fear we dare not fear,

That fear of fear itself, or fear of other’s fear,

Such fear as ends

In passionate untruth, self-justifying falsehood without end?

Demonic fear

Of individual guilt, of being caught, of doing wrong,

And fear of failure or of being found a fool,

And fear of anything that might contrast with me

And thus reveal my insufficiency,

My lack, my weakness, my inferiority,

In showing up my difference from itself;

Fear of uncertainty and loss, fear of all change,

Fear of all strangeness and all strangers; and above all else the fear

Of Love, of being loved, of being asked for love,

Of being loved yet knowing one has no love to return;

Fear of forgiveness —

Fear of that love which is so great it can forgive

And the exhausting fear of Death and Mystery,

The Mystery of Death, of Life and Death,

The huge appalling Mystery of everything;

Arid fear of Nothing,

Yes, after all the fear of Nothing really,

Fear of Nothing, Nothing

Fear of Nothing, Nothing, absolutely Nothing.

In Britain, much contemporary poetry is totally trivial. It is thought in literary circles, in modern art too, that the trivial, the throwaway is the postmodern profound. Not so. The example of David Gascoyne, coming in from the cold, shows us what is at stake. He is one of the few English poets who have anything to teach us in the current crisis. Having died on Sunday 25th November 2001, he was alive for the defining moment of the 21st century. I would like to know his take on the events of 9-11. It is good for humanity that he saw it, exiting Christendom, even if it was too late for him to write about it.

Niall McDevitt is the author of two critically acclaimed poetry collections, ‘b/w’ (Waterloo Press, 2010) and ‘Porterloo’ (International Times, 2012). He organised the event ‘An Evening Without David Gascoyne’ in 2012, featuring Hilary Davies, Robert Fraser and Jeremy Reed. (This essay was taken from McDevitt’s second book; ‘Porterloo’.